A Stroll in the Garden: A Brief History of the Rose without Thorns

February 16, 2020

By Laura Lieber

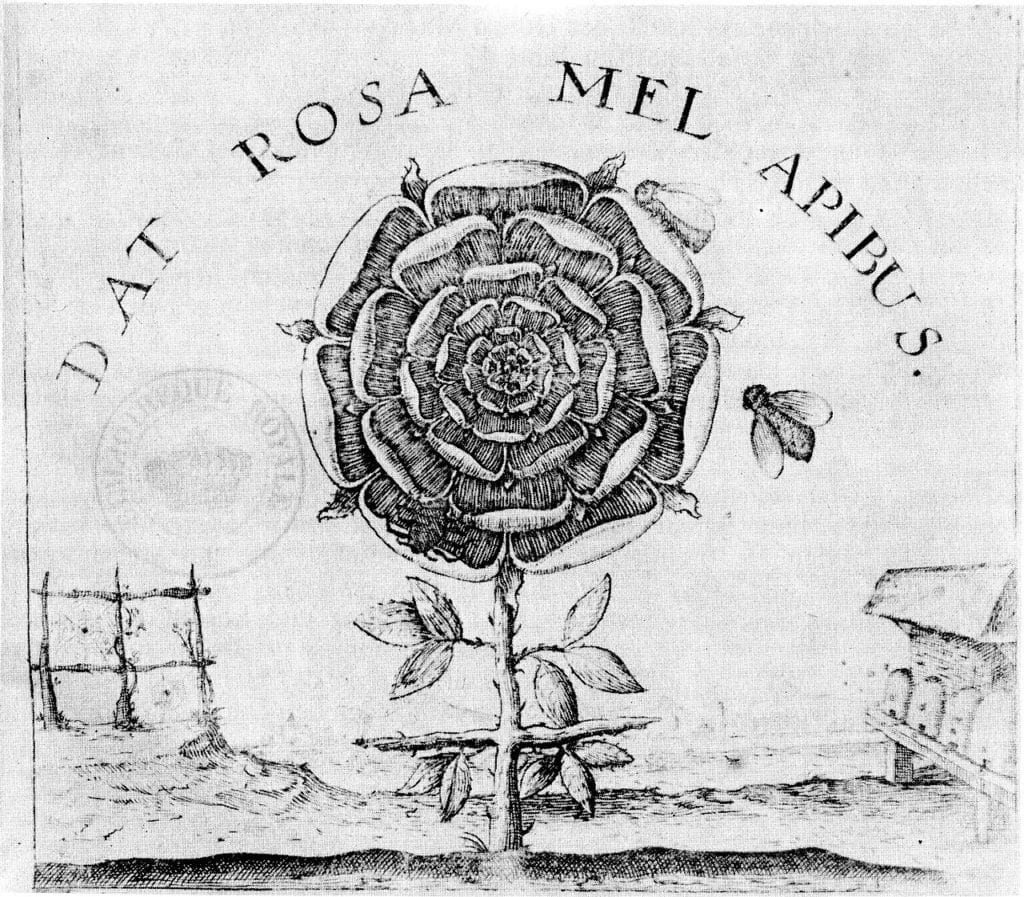

According to Ambrose of Milan, the Church Father who lived in the fourth century (over a millennium before English composer Thomas Tallis), roses first grew in the Garden of Eden, and those first roses were entirely without thorns. Only after Adam and Eve disobeyed God and were expelled from the Garden did these blossoms acquire their prickly defenses. Rose blossoms, with their beauty and aroma, serve as enduring reminders of Paradise, even as roses’ thorns remind us that Paradise has been lost. According to Ambrose, the Virgin Mary is “the rose without thorns”: born free of Original Sin, she was free of the thorns — the sins — that had pricked humankind since Eve ate from the apple.

Over the centuries after Ambrose, Mary’s association with the rose grew stronger and people found new ways to express the symbolism. In the twelfth century, cathedrals came to include a rose window at the end of a transept or above the entrance, dedicated to the Virgin. A century later, according to tradition, Saint Dominic instituted the Rosary, a series of prayers to the Virgin (prayed using beads which may be made of or scented with rose petals), named for the garlands of roses worn in heaven. As Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153) wrote, “Eve was a thorn, wounding, bringing death to all; in Mary we see a rose, soothing everybody’s hurts, giving the destiny of salvation back to all.”

The rose, of course, possessed rich and evocative symbolism centuries before Ambrose linked it to the Virgin Mary. Among the Greeks, the five-petaled rose was a symbol of Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, while among the Romans it became associated with both Venus and the goddess of spring, Persephone. The Roman funerary festival of Rosalia or Rosaria, sometimes called dies rosationis (“day of rose-adornment”) was celebrated in early summer (usually in May); graves and memorials would be decorated with garlands of roses (or, alternatively, violets), in part because of the association of blood and blossoms in Greco-Roman tradition, such as the legend that roses bloomed from the blood of Adonis — a mythical figure whose name, related to the Hebrew for “Lord” (adon), indicates his Semitic roots. Roses thus became associated with heaven and the afterlife in Christianity, and red roses specifically symbolized martyrs. By the sixth century CE, we have records of celebrations of a “Day of the Roses” — a descendant of the Roman Rosalia — among the mixed Christian and non-Christian population of Gaza.

Among Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Middle Ages, the rose (with its thorns) was a potent symbol of love — its ephemeral pleasures and hidden pains.

For all its rich history of symbolism in the Greco-Roman world, the rose is not a common flower in the Hebrew Bible. Indeed, the Bible does not mention flowers often — thorns are a far more common symbol. This relative lack of floral imagery makes the sensual imagery in the Song of Songs (also known as the Song of Solomon or Canticles) that much more striking. In the Song, the female speaker compares herself to a rose: “I am a blossom of the Sharon, a rose (or: lily) of the valley” (Song 2:1), a self-image which her lover affirms: “like a rose among thorns, so is my darling among the maidens” (Song 2:2). The woman also compares other women to roses, imagining her rivals as a kind of garden in whose midst the male lover has roamed and sampled: “My beloved is mine and I am his, he who browses among the roses” (Song 2:16; see also Song 6:2-3). Finally, both lovers compare parts of their bodies to roses: the woman describes her lover as having “lips like roses, dripping flowing myrrh” (Song 5:13); and, just as suggestively, the male lover tells his beloved, “Your belly is a heap of wheat, hedged about with roses” (Song 7:3). The rose, with its thorns, appeals to the senses of scent, sight, and touch, and is not limited to a single sex — or to virgins.

In post-biblical Jewish sources, the rose often symbolizes the people of Israel, and while the thorns symbolize hostile nations. It is striking that the Zohar (“the book of Splendor”), the central work of medieval Jewish mysticism, opens with an explication of Song 2:2, “Rabbi Hezekiah opened his discourse, ‘It is written, “Like a rose among thorns” — Who is the rose? That rose is the Assembly of Israel.’” Among Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Middle Ages, the rose (with its thorns) was a potent symbol of love — its ephemeral pleasures and hidden pains. Poetry emerging from these traditions can often challenge the distinction between the “secular” and the “sacred,” as poets often playfully blur the boundaries between the God they worship and the mortals they desire. An entire genre of “flower poems” emerged in medieval Andalusia, written in Hebrew, Judeo-Arabic, and Arabic; these works in turn shaped the European tradition of the troubadours and the Christian courts of Europe, including their music and art. It seems likely that roses themselves — and what might be termed “rose-garden culture” — found their way into the European landscape along this pathway from southern Spain. The famed gardens of al-Zahra and al-Hambra, and the broader Mediterranean world, held the seeds, both real and metaphorical, for the transmission of the rose blossom and its rich tradition of symbolism.

Thomas Tallis’ song, “Ave, Rosa Sine Spinis,” participates in a long tradition of flower poetry, which, in the Christian tradition of hymnody, tends to focus on Mary, herself an object of love and desire. Ambrose of Milan in the fourth century and the poet Coelius Sedulius, writing a century later, both composed hymns celebrating Mary as the “antidote” to Eve: Eve, through sin, endowed the rose with thorns; Mary, born in and giving birth to the essence of purity, offered a thorn-free image of redemption. The bloom of the rose represents the triumph of life over the suffering and doom of mortality’s thorns. Tallis’ hymn, growing from the soil of early Christianity and nourished by the inspiration of medieval tradition, now brought to Durham by Duke Performances, represents a distinctive blossoming of this imagery in the arts.

From the third century of the common era to the present day, the symbolism of the rose endures and inspires. Examples abound. In the Jewish imagination, floral poetry lives on in the lyrics of “An Evening of Roses” (erev shel shoshanim). This popular song’s lyrics are written in modern Israeli Hebrew set to a Middle Eastern (mizrachi) melody; every line resonates with allusions to the Song of Songs, and the sacred and secular blur together. The Moroccan Arabic folksong, “The Young Rose” (al-warda as-sghira), likewise employs the symbolism of rose and thorns, applying them to a human love affair that is ending. It opens, “It’s all over now — you’ve grown thorns; it’s done, and you’ve forgotten my goodness.” In western Christianity, “floral poetry” lives on, as well; the imagery easy to find in contemporary Gospel songs, country music, and bluegrass ballads. Of all “modern” works, however, the lyrical poem “Rosa Mystica” by the Victorian poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889) perhaps offers the finest book-end to Ambrose of Milan, our first Christian rose-poet; here the first, fourth, and final stanzas are quoted:

The rose in a mystery, where is it found?

Is it anything true? Does it grow upon ground? —

It was made of earth’s mould but it went from men’s eyes

And its place is a secret and shut in the skies.

In the gardens of God, in the daylight divine

Find me a place by thee, mother of mine.

Tell me the name now, tell me its name.

The heart guesses easily: is it the same? —

Mary the Virgin, well the heart knows,

She is the mystery, she is that rose.

In the gardens of God, in the daylight divine

I shall come home to thee, mother of mine.

Does it smell sweet too in that holy place? —

Sweet unto God, and the sweetness is grace:

O Breath of it bathes great heaven above

In grace that is charity, grace that is love.

To thy breast, to thy rest, to thy glory divine

Draw me by charity, mother of mine.

Here, as in Ambrose, we find Mary identified as her signature flower: “She is that rose.” A maiden in the Garden, her breath is that of heaven and her touch brings only healing and relief. As we stroll with Hopkins, we glimpse a bit of paradise, and we encounter only the lovely grace of heavenly scent and tender petals, and are spared the familiar, painful prick of the thorn.

___

Laura S. Lieber is Professor of Religious Studies at Duke University, and author of A Vocabulary of Desire: The Song of Songs in the Early Synagogue (Brill, 2014).